“People make fun of me for talking about death at parties.” “Me too!”

Also, some uplifting-ish political news

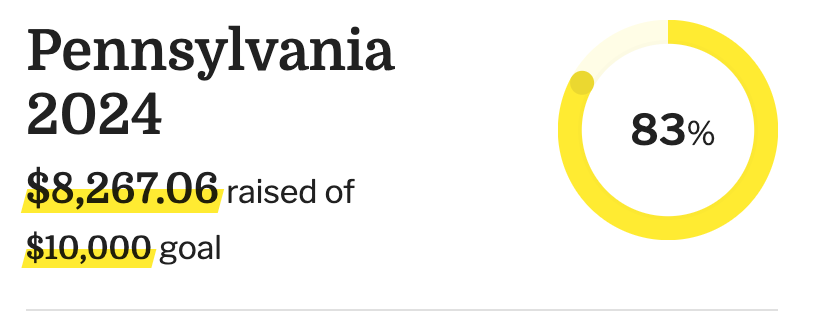

Before I get to today’s issue, I just want to share something pretty amazing. Since last week’s issue rolling out our States Project Giving Circle to benefit Pennsylvania Democrats, the total raised went from $1,231.06 to this, as I write:

Thank you, thank you to everyone who chipped in, spread the word, and started taking steps to start your own Giving Circle (if you’ve begun one, please let me know so I can donate and spread the word.) I really can’t take living in such interesting times, and having this to focus on and knowing that these donations will actually make a difference has helped me keep my head on straight, and I have heard the same from others. Hope you join the Circle at some point if you haven’t yet.

*

Early this year, it seemed like I was sending out a lot of sympathy cards to people who had lost a parent. I was pondering what it’s like to try to care for a growing list of grieving friends when you’re in a season when there are a lot of grieving friends. This made me think of people who make their lives about keeping death at the top of their minds—death doulas.

Conveniently, my friend Erica Reid Gerdes is a trained death doula in Chicago who has assisted over 25 families in active death support, advance planning, making funeral arrangements, doing research, facilitating conversations, and legacy work. She trained as part of Alua Arthur’s Going with Grace Institute, as did Patrice Dwyer, a death doula based in Kingston, Jamaica, who worked with over 25 families since she was trained. I spoke with them both earlier this spring to learn more about how their work differs from hospice, what you say when you’re visiting a dying person and find yourself with nothing to say, being a bedside bouncer, and the death doula business model.

The first chunk of the interview, which has been condensed and edited from a longer conversation, is available for you all, but paid subscribers get the delicious meatloaf end of it (so think about joining if you want to read the whole thing!)

*

What brought you into the field of death work?

Patrice: I felt called to it. I had an aunt who was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. I spent a lot of time with her, sitting bedside with her and doing simple things, trying to engage her in a little conversation, cutting fingernails and toenails.

Then, at 16, I lost a close friend. then I lost my cousin when he was 21, and I was 18. That was sudden as well. I’ve been processing that for years. There was a period when I was going through a space of fear of death from when I was a very young child, maybe because I saw a lot of it and nobody explained it. I realized there were aspects to end-of-life care that people weren’t paying close attention to, various things that were left undone, and confusion from family near the end of life around things like burial choices and medical choices.

There was this series called Time of Death on Showtime. It featured people approaching the end of life who had agreed to have their lives filmed all the way through. I watched it, and I was fascinated. It was on that program that I first saw Alua Arthur.

The place close to my heart is around supporting people in the dying process, preparing and supporting families, and especially for the people who come into my space who are facing serious diagnoses to start thinking about what it is to plan. My thing is, “Let’s start talking to people about planning and all of that before they even get sick.” I’ve had the privilege now of working with a few people who are end of life with psilocybin.

Erica: I had a lot of death in my youth. My beloved dance teacher died when I was 13. At her funeral, where she had left messages for some of her students saying, “You’re going to be great; you’re a great dancer.” I did not get one of those. That affected a good deal of my life because she was my hero. Now, when people say, “Oh, I want to leave messages to people,” I’m like, “If you’re going to have them read at a funeral, have it be for your family. If it’s to people that are important to you, give it to them in private, because we never know what we mean to other people.”

Watching my great-grandmother’s death and then my dad’s cancer, and then my mom’s illness, and then having a number of friends also go through cancer journeys, I would sit with them through chemo and sit with them when they were homesick. A joke a lot of us death doulas have is that we’re the people who always talk about death at parties. You go to your training, and then everyone’s like, “People make fun of me for talking about death at parties.” You’re like, “Me too.”

A couple of years ago, a friend of mine sent me an article about Alua Arthur. I signed up for her training the next day. That training changed my life because it gave me better tools than the work I was already doing. It gave me the skills and confidence to go into a house that has nobody in it that I know and talk to them and offer support there.

How does this work compare to hospice care as well as birth and postpartum doulas?

Erica: We don’t provide any medical support; we provide logistical support on the nitty-gritty of what needs to get done so that the family can focus on grieving and being with their loved one. We often work with hospice, and when I’ve talked with hospice nurses, they’re like, “Oh, we love death doulas” because they’re spread so thin, and only they’re there for just a few minutes to check in to make sure that the dying person’s not in pain or just to check on vitals. We can really have the space to sit and assess the situation and see what’s needed.

Sometimes, it’s that you just need to listen. Sometimes it’s that you need to wash dishes. Sometimes it’s that you need to go to the funeral home to make arrangements so that the partner, a family member of the person who’s dying, doesn’t have to leave. There are a number of things that we as doulas can support, whether it’s advanced planning, doing a legacy project, writing a eulogy, writing an obituary, and then sitting at active bedside, having conversations, just getting people to accept this. A lot of times, there are high emotions at the end of life, and people don’t always communicate or listen. Everything is so intense. We can come in and say, “Let’s have the space to share what you want to share.”

We can tend to be like, “Don’t give up.” Well, it’s not giving up. We’re all going to die. It’s just becoming comfortable with it when it is your time to go. Mostly, as doulas, we ask a lot of questions. We don’t put any of our feelings in or prompt anyone to do any certain things. It’s a lot of reflecting back on what we hear and asking questions that can hopefully trigger an epiphany. That sounds pretty huge, but sometimes it is that, or sometimes it’s just like, “Oh yeah, I don’t know. I want to be cremated.” People don’t think about those sorts of things.

We’re all in a state of transition. I call myself a transition doula because some folks will have a block on “death doula” or “end life doula” because they’re like, “Well, I’m not dying,” or, “I’m trying to stay alive,” You hear the phrase life portals: birth is one, death is one. There is a similarity in helping usher one creature from one plane of existence to another in both regards. On the death side of things, we can be there to hold that space for folks to make it a more meaningful experience than oftentimes in our clinical, medical, corporate society will allow us to.

What is your business model currently?

Erica: When people ask, “What’s your biggest challenge of being a death doula?” It’s what to charge. It is such emotional work; it feels weird to be like, “Now pay me,” but also, we’re providing a valuable skill, and we do have to pay our bills. On my website, I say that my work is “pay what you can.” I want to be equitable for everyone. There is a sliding scale if you want to use that as a guide, but I’ll accept any amount.

I’ve had people say, “Well, let’s agree on this amount per hour.” I’ll say, “Great.” Sometimes, I’ll support a whole family from start to finish, and then they’ll just give me what they can after and say, “Is this okay?” The answer is always yes. I also accept donations so that if people want to just give extra because that will help support community care in the future, it’ll support me so that I can support other people who maybe don’t have the means to do it.

Patrice: I’ve not charged some people. What I have charged for and have an hourly rate for is the planning process. One of the ways I work is I’ll sell them a copy of my workbook, and that comes with an initial consultation, the price, and the value of the work. Sometimes, I also wear a patient navigator hat. I will sometimes charge for that and not necessarily in the space of being a death doula. But in terms of bedside and all of that, it’s case by case.

What’s an example of how you put your training to work?

Erica: A lot of the training asks you to come to terms with your own feelings of death and how you want to navigate through these spaces. Doing that does change how you see things. That helps you explore with a client or family; then, we can go and be able to ask questions in the home. The other thing is just using certain terms and resources. I’m reading Death Glitch right now about your online presence after you die and how it’s left. We’re all so online, so all of these things are just going to help as it becomes more of an issue in the future.

Patrice: What the training taught us was how to be a good space holder. It means you have an understanding of what makes you tick and what triggers you. Because when you’re holding space for people, anything can show up, you have to know where that boundary is between your stuff and their stuff.

Erica: Boundaries are a huge one because if you’re ever in a situation where you’re not comfortable, then you’re not going to serve the client or the family. I’ve learned that, especially since my mom died, where my boundaries are in certain regards with things that remind me of my experience. Can I support someone through it? Yes. Can I go into those spaces and do it myself? Absolutely not. I still have a lot of work I need to do on myself, but I’m so far removed from my father’s death that going into that world [of cancer], I’m very comfortable because I’ve done that work. You learn a lot about what you can and can’t handle. When the client comes to you, it helps inform you if this is somebody that you can support or if it’s somebody that you need to get another colleague to help.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Evil Witches Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.